What it means to choose your own death

My thoughts as a death doula and former hospice director on one of the most ethically loaded, emotionally charged topics within the deathcare space: Medical Aid in Dying (MAID)

Note: Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) is a deeply personal topic. My intention isn’t to persuade, but to spread awareness, share what I’m learning, and spark thoughtful dialogue. Wherever you stand, or if you’re not sure yet, I hope this gives you something to sit with.

As a death doula, I often receive inquiries and referrals from people on hospice who are considering the option of choosing their own death, and would like to know more about the possibility of utilizing Medical Aid in Dying (MAID), a medical practice that allows terminally ill patients to request from their doctor a medication that will allow them to die peacefully in their sleep.

The first time I encountered this in real life was at the hospice I worked at on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. A resident wanted to utilize MAID, but it wasn’t legal in MA, so we couldn’t help her. All we could do was educate her on her right to voluntarily stop eating and drinking (also known as VSED). What made the situation even more heartbreaking was that the resident had dementia, so I had to have the conversation with her multiple times. Each time she was just as devastated.

Now, I live and work in Colorado, where it is legal. This past week, I had an exciting opportunity to hear from people who have actually been doing the work, and to learn firsthand about the experience, challenges, and ethical considerations. After attending a two-day conference hosted by End-of-Life Options Colorado, a nonprofit dedicated to educating and supporting people around MAID, I have a much deeper understanding of this complicated and important issue that I’d like to share.

Whether you’ve thought deeply about it or managed to keep it out of sight, out of mind, the movement towards greater patient autonomy in end-of-life choices is changing how people die, grieve, and care for dying patients. Before we go further, let’s define what we’re talking about because—depending on who you are talking to and what country you’re in—you might get different answers.

So, what is MAID?

As I understand it, Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) is an end-of-life option for people with a terminal diagnosis and a prognosis of six months or less to live. In the U.S., where it’s legal in select states, eligibility requires that a person be 18 or older, of sound mind, evaluated by at least two physicians, and able to self-administer the medication (typically a compound referred to as DDMA or DDMAPh), either orally or rectally.

In other countries, like Switzerland, the rules are different. A terminal diagnosis isn’t required—only a demonstration of “unbearable suffering.” That broader definition is deeply controversial and raises complex ethical questions. In countries like the Netherlands and Canada, there is concern that growing numbers of young suicidal people (without a terminal diagnosis) are asking for help to die.

The medication itself usually works quickly. Within minutes, the person falls into a deep sleep. Over the next few hours, the heart slows, and death follows. It is often described as a peaceful and safe death, with the person dying on a day they chose, in a setting they chose, with the people they chose beside them.

For many, choosing MAID is not about giving up. It’s about reclaiming agency in the face of death. And it offers an alternative to what might otherwise be a long, painful, traumatizing, or isolating death for both the person dying and the people who remain.

As Anita Hannig, a cultural anthropologist and author of The Day I Die: The Untold Story of Assisted Dying in America, explains, MAID is not suicide. Instead, it is “a medical response to the devastating reality of terminal illness…. It is a distinct category of end-of-life care.”

The practice first began in Oregon in 1997, when voters passed the Death with Dignity Act, the first law of its kind in the country. It came after years of advocacy, a growing backlash against medicalized prolonged deaths, and the national debate around figures like Jack Kevorkian, who publicly assisted more than 100 deaths in the 1990s and served time in prison for it. But the roots of this movement go back much further. Ancient Roman philosophers like Seneca saw voluntary death as a rational choice in old age or illness. And Switzerland legalized assisted death back in 1942.

So this isn’t a new question. But what is new is how it’s showing up in modern medicine and end-of-life care.

In America, the main qualification for MAID is a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months or less to live (among other criteria). Today, it is legal in 11 U.S. states and counting. Earlier this week, New York State made headlines by passing the Medical Aid in Dying Act (S138), in the Senate, a landmark moment nearly a decade in the making. The bill now awaits Governor Kathy Hochul’s final approval. If signed into law, New York would become the 12th U.S. jurisdiction to legalize MAID—and the first to do so with no mandatory waiting period. Additionally, as the New York Times notes, the bill’s lack of residency requirements “opens the door for terminally ill patients from out of state to come to New York to end their lives.”

This is a BIG deal! For many New Yorkers who’ve spent years lobbying, testifying, and waiting, it represents a hard-won expansion of agency and choice at the end of life. But it’s also stirred deep controversy, raising important questions about safeguards, equity, and what it means to die with dignity.

Exploring MAID raised a central question for me: When suffering starts to outweigh the value of life, who gets to decide how the story ends?

There are so many questions that surround this one. What does it really mean to choose your own death? Who should be able to do so? Should MAID be legal, and what should the parameters be? And if you decide you want the option to choose your own death, what does that choice demand of everyone else involved—some of whom might not want to be?

It’s easy to ponder MAID in a detached or theoretical way, and forget that what it actually means, for providers or caregivers, is playing an active role in someone else’s death.

At the conference, I listened to doctors, nurses, and doulas share their experiences with patients and clients. People shared real stories—vulnerable, gracious, unfiltered—about what had gone wrong, what had gone right, and what they’d learned the hard way. For instance, the importance of giving someone sorbet before and after ingestion to mask the foul taste of the medication, instead of ice cream, because the cream makes the medication work more slowly, resulting in a longer death. (On average, it takes a few minutes to fall asleep and about two hours to fully die, but there are outliers.)

One hospice nurse shared a heartbreaking story that ended her career. At the time, she was caring for a patient who had been approved for MAID and was ready to take the medication. But her hospice had a strict policy: no staff could be in the room during ingestion. That day, the patient—crying, scared, and alone—begged the nurse to stay in the room. So she did. She sat beside the bed, held her hand, and witnessed her final moments. The patient died peacefully, and then the nurse was fired. Her story is a powerful reminder of just how deeply human and incredibly complex this topic is.

Alongside the emotional weight, we also covered logistics: who is eligible, how they receive the medicine, what the medication is made of, and how to help prepare the patient and the people they love. Practice, it turns out, is important: self-ingestion (oral or rectal) is a requirement of MAID, so it’s important to go over a checklist of things to help reduce mistakes and anxiety.

After attending the MAID conference, I watched a training video for care providers that brought the process to life, reenacting the full protocol from start to finish for a patient ingesting the medication. Despite the clearly low production value, the film made me surprisingly emotional.

I found myself asking: Could I actually help someone do this? (Keep reading to find out.)

If you didn’t choose to be born, should you be able to choose how you die?

During a conversation about eligibility, a nurse shared a story about a patient in her nineties who desperately wanted MAID. However, her diagnosis—eczema—wasn’t terminal, so she didn’t qualify. Then someone else chimed in, half-joking but also serious: “Isn’t just being in your 90s a terminal diagnosis?”

Everyone laughed, and then got quiet. When you think about it, isn’t just being a human a terminal diagnosis? It made me think of the words of Buddhist scholar Anne Klein: “Life is a party on death row.”

And yet, we gatekeep access to death more fiercely than we guard access to life. What I mean by that is: We make people jump through endless hoops to prove they’re “sick enough” or “suffering enough” to qualify for MAID. We treat the choice to die with intense suspicion, moral panic, and legal barriers (and of course, it should be treated with the utmost respect and caution).

But the problem is, we don’t treat life with the same reverence. We don’t ensure people have access to the basic things that make life livable: housing, healthcare, mental health support, disability services, childcare, etc. If someone is poor, isolated, or disabled, we don’t rush in to offer everything they need to thrive. In fact, we often fail them… so why should we be surprised when some of them wish to die? Let's hope this is not a glimpse of what's to come.

So we’re left with this cruel irony: We ask people to fight harder for the right to die than we ever helped them live. That’s the system we’ve built. That’s what we need to reckon with, and I hope we can reckon with it together.

It’s this question of the value of life where things get ethically murky. Some people view MAID as a form of assisted suicide—morally wrong, a sin, something no person should ever participate in. Others see it as an act of mercy and a basic human right.

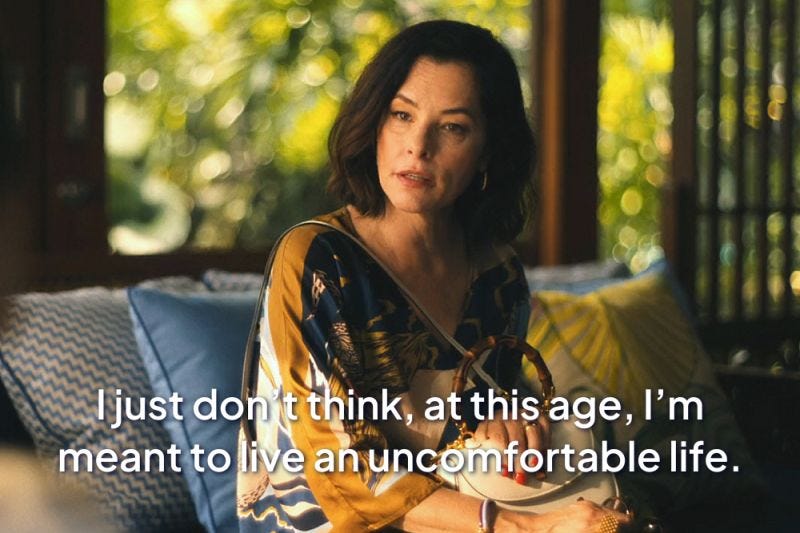

As my aunt, a retired healthcare professional, so eloquently put it: “People don’t want to die—they want to live comfortably. And that’s no longer possible sometimes.” Her sentiment reminded me of a scene from Season Three of White Lotus, where the character Victoria Ratcliff (played brilliantly by Parker Posey), a rich southern housewife, muses about what she’d do if she lost everything:

“I don’t know if I would want to live. I just don’t think that at this age, I’m meant to live an uncomfortable life. I don’t have the will.”

This line made me chuckle when I heard it, but underneath the laugh, there’s something real and sobering about what she says. When it comes to terminal illness, not everyone has the will to fight through a long decline. Not everyone wants to. So the question is: Who gets to decide if they should have to?

And while that question—who gets to decide—is deeply personal, it’s also political because context matters.

In the U.K., new legislation legalizing MAID is arriving at the exact same time as massive welfare cuts. Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson, a Paralympian and member of the House of Lords, recently warned that disabled people may be pushed toward choosing death, not out of autonomy, but desperation.

“If your benefits are cut, making life intolerable,” she said, “it’s obvious more people will feel forced down this route to end their lives early.”

Here in the U.S., threats to cut Medicare, Medicaid, and disability support raise similar concerns. If we legalize the right to die but deny people the basic care they need to live and age well, what kind of “choice” is that?

A Canadian study of MAID providers offers a sobering echo: while most patients requesting MAID met the criteria, some did so out of loneliness and poverty—unmet needs that point more to a failure of society than a failure of medicine. As one provider put it, honoring these requests meant carrying the weight of knowing “some of their suffering was due to society’s failure to provide for them.”

Where do you stand?

It’s worth asking yourself: If you were suffering and knew you were going to die soon, do you think you should have the authority to decide when you’re ready to go? It’s an important question for each of us to contemplate.

MAID is one of those polarizing issues that is likely to always yield strong disagreement. Like abortion and gun rights, it touches on questions of autonomy and control in ways that provoke deep moral, emotional, and spiritual reactions.

While there’s so much more to say about this topic, I’ve done my best to outline what I believe are the major viewpoints surrounding this issue. Maybe you already know where you stand. Maybe not. Either way, I hope the following summary helps you contemplate this important topic further:

Staunch supporters believe MAID is a humane and ethical option—an act of mercy, not murder. They view it as a means to alleviate suffering and restore dignity. You’ve likely heard the pet euthanasia argument: We wouldn’t let our dog suffer like this, so why do we let people?

As State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal, a Manhattan Democrat, recently put it: “It isn’t about ending a person’s life, but shortening their death.” And one New York advocate put it simply: 'A prescription’s a whole lot nicer than a shotgun.' Painfully blunt, but it captures something essential—MAID isn’t just about ending pain. It’s about control, safety, and choosing how that ending happens, and making it as trauma-free as possible for everyone involved.

For many who pursue MAID, that’s all they want: the peace of mind that comes from knowing they could take the medication, whether or not they ever do. However, even within this camp, there is considerable debate, including the question of which method should be used (Liquid? A Sarco Pod? Or something else entirely). Additionally, other considerations include: Who should be able to prescribe MAID (e.g., palliative care, hospice, or family doctors)? What should the prescription be called (a cocktail, poison, or medication, etc)? How long should the waiting period for assessment be? I could keep going, but you get my point.

Opponents are anti-MAID on moral or religious grounds. They may see it as suicide—plain and simple—and believe life should never be deliberately ended, regardless of suffering. In Christian traditions, for example, there's a belief in the sanctity of life; that life is a gift only God can give or take away.

Others worry about the slippery slope: If we normalize death as a medical solution to pain, what happens when the criteria get murky? What if we start devaluing the lives of the elderly, disabled, or mentally ill? Some disability rights activists fear that MAID sends a dangerous message: that some lives are less worth living.

And more recently, some critics argue the New York bill goes too far, eliminating the waiting period that other states require. Without that built-in pause, they worry decisions could be made in moments of despair or fear, without time for reflection or support.

The “I’m not sure” camp consists of people who don’t oppose the idea in theory, but also feel uneasy about what it means in practice. What are the risks (potential coercion, especially under financial or family pressures)? What are the safeguards? Would I ever do this? Could I support someone else who does?

If that’s you, check out Crux—an app my friend built to help you clarify your opinion on today’s top issue and capture it in a simple, shareable snapshot. Today’s daily crux is about MAID, and it’s a great place to start to explore your opinion.

Since I promised to tell you, here’s what I personally think (at this time), based on my experiences as a death doula and former hospice director, as well as my own personal beliefs and moral frameworks:

I believe the MAID should only be available to terminally ill patients with a prognosis of six months or less to live, and that a holistic team should be in place to attend to the spiritual, emotional, and physical needs of the patient and the people they love. This already exists primarily in hospice, which is why I believe a hospice doctor should prescribe the medication.

Would I be willing to support a client through MAID? Probably.

Would I be willing to mix the meds and hand them the cup? I don’t know yet.

I won’t pretend certainty when it comes to understanding why someone would want to end their life, and what is really at stake. I’ve lived through some very dark moments. After my mom died, I went skydiving and remember feeling absolutely no fear—because I truly felt like it didn’t matter whether I lived or died. I tasted the edge, but chose to step back, and I’m so glad I did; or perhaps my parachute chose for me (thank you, parachute).

It would take time and trust for me to guide a client through MAID. I’d need to know the person, understand the situation, and even then, I might still hesitate. But the stories I’ve heard from doulas, nurses, families—they’ve softened my fear. They’ve made me think: maybe I could help someone through this.

Here’s what I keep coming back to: We prepare for weddings, births, graduations, and retirement with such care. So why wouldn’t we approach death the same way? To me, the most radical thing about MAID isn’t that it allows someone to choose death. It’s that it invites us to imagine what a peaceful death looks like. Because imagining a peaceful death is an act of rebellion in a culture that pretends death doesn’t exist.

In a culture that treats death as a failure, when someone says: I want to die on my own terms, in my own time, surrounded by people I love, they are not just choosing death—they’re reclaiming it.

Whether you are for or against MAID, or undecided, it’s worth contemplating: What would you want your death day to look like? The view out the window. The smell in the room. The final taste on your lips. The music playing. The people around you.

Still have questions?

While I’ve touched on some of the big ones here, there’s so much more to discuss. Rather than trying to cram it all into this post (if you’re still reading this—thank you), here are a few resources to consider:

For the nuts and bolts—from who qualifies, to how it works—start with the FAQ section of Death With Dignity.

If you enjoy documentaries, Take Me Out Feet First is a must watch.

If you're a clinician, caregiver, or just someone who wants to understand the clinical side of this practice, the Academy of Aid-in-Dying Medicine is the go-to. They offer training, research, and practical guidance for everyone from doctors to death doulas, and they’re leading the way in building real standards of care for aid-in-dying practices.

And if your questions are more existential than logistical, that’s what I’m here for! Comment and share what’s on your mind or bring it to our next Death Over Coffee on Sunday, June 29th (upgrade to a paid membership to attend!), where we talk about all the stuff no one wants to talk about—together.

— Maura

This may be too controversial. And not everyone will understand this belief. So it’s difficult sharing this. But I believe when it comes to our death, it’s our own free will. It’s our soul’s choice when we leave this physical earth. Regardless of the manner of death (suicide, cancer, accidents, MAID, heart attack) we choose when it’s our time to leave. Not God, but me. Or you. Or the thousands of people around the world dying this moment.

Many people will push back and say, “what about murder? Was it their choice?!

And my answer is yes. Sadly, yes. 💔

It goes much deeper than most can comprehend.

We come here on earth to experience love, joy, grief, fear, hate, happiness, envy. All the things. Which includes when we die.

We think death is the worst outcome anyone can experience. What if death is a gift? A gift the for the person who died and a gift for the living. This life is so beautiful and sacred. And if someone chooses to not suffer towards the end of a terminal illness, that is their choice. There is no right or wrong way to die.

This is most definitely a subjective opinion. Thanks for giving me the space.

What you’re writing is so important. And I am here for it.

Appreciate this article, Maura. My grandmother died a slow, painful death that was incredibly hard for everyone involved. No one should have to die like that, and despite the complications and challenges that come with MAID, I believe it is worth finding a way to make work. Your considerations and insights here are a great contribution to the space.