The wisdom of dying (and grieving) like the Irish

And how you can embrace death with both reverence and rowdiness!

As a person of Irish ancestry on both sides of my family, I’ve attended my fair share of Irish-American funerals (comes with the territory when you’ve got a big Catholic family), but I’ll never forget the first time I saw a dead body—my grandmother’s.

My grandmother, affectionately known as Nana, lay in a plush coffin, hands folded neatly over a rosary, her face smooth and waxy—almost too perfect. The embalmers had done their work well. She looked familiar, but not quite real, like a delicate replica of herself, preserved in time. It was Nana, and yet, it wasn’t.

I stared at her for a long time, waiting for something. What, I wasn’t sure. A moment of revelation? A sense of closure? But mostly, it just felt… strange.

When my grandmother died, her funeral followed a structure familiar to many Irish-American families. Her wake lasted multiple days, just as the old traditions dictated. But instead of being held in the home, as it might have been in another era, it took place in a funeral home. Upon entering, guests were handed a small card with her face on one side and an Irish blessing on the other. Inside, the drab funeral room was filled with chairs arranged neatly in rows, with an open casket at the front. I remember watching people file in, shaking hands with my grandpa, my mom, aunts, and uncles, then kneeling before her casket, whispering prayers or silently paying their respects. Then, they stepped back, joining family and friends in quiet conversation. It all felt hushed, muted, restrained.

Something was missing—the rowdiness, the irreverent humor I’d heard about in old stories of traditional Irish wakes. None of it was there. No one played pranks or sang songs, no one knocked back a drink in her honor. It felt entirely too structured, too quiet…as if everyone was waiting for some sort of afterparty to let loose a bit.

It wasn’t until I asked my mom to recall her own memories of her mother’s funeral that she described drinking and laughing and lots of storytelling, out in the parking lot and then at the luncheon after the funeral mass.

Yep, there was an afterparty that I, as a 20-year-old, missed.

But the Irish wake is more than a balancing act of mourning and celebration—it’s an ancient guide to living and dying, a way to remind ourselves and teach our children that while death is ordinary, life is extraordinary. In embracing death together, we relearn the oldest human lessons: how to love, how to carry each other through loss, and ultimately, how to live.

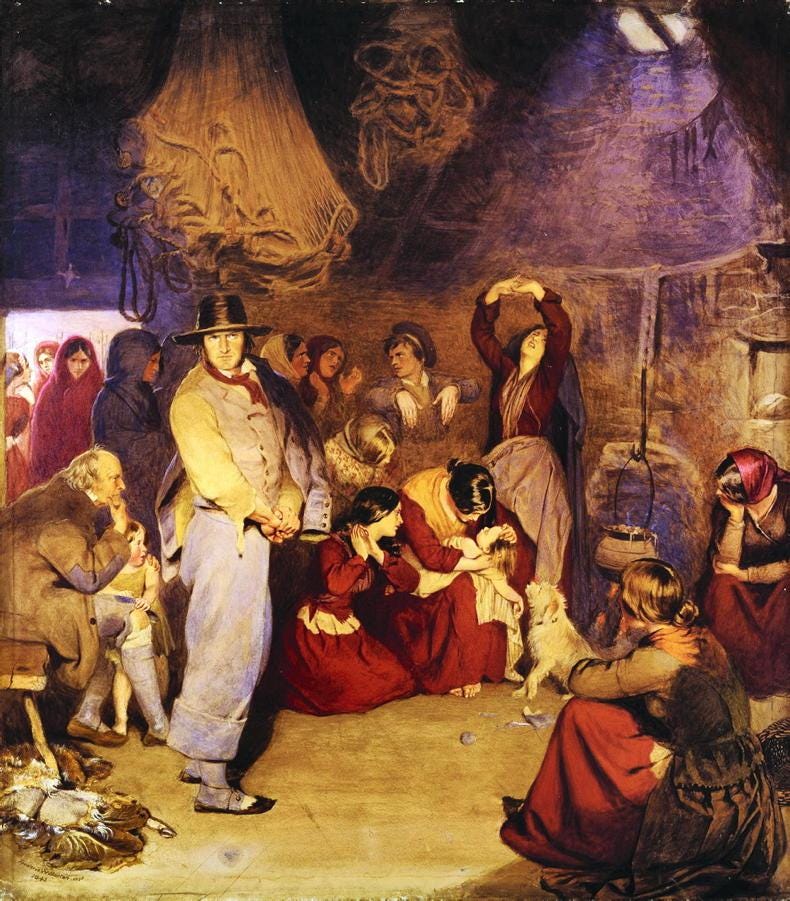

How the Irish do death

Ireland has long been a land shaped by hardship—oppression, famine, discrimination, and poverty—and a culture of strong, spirited people who have learned to celebrate and find joy in the midst of any adversity. Perhaps because of this history, the Irish have never quite had the same fear of death that’s pervasive in Western cultures. Instead, they have met death with open arms, through ritual, stories, and humor. The traditional Irish wake is one of the most enduring examples of this: a paradox of mourning and festivity where grief and laughter coexist, and where death is not only acknowledged but embraced.

Where we Americans sanitize death and keep it behind closed doors—and expect grief to be neatly contained within a funeral service and a few weeks of mourning before life resumes—the Irish allow this experience to be messy, loud, and most importantly, shared. Particularly in rural communities in Ireland, death was never solely a private matter. It was communal, it was embodied, and it was fully witnessed—without shame or holding back. The wake wasn’t just about mourning; it was about giving grief—and death—a voice.

And in doing so, it gave us something that we, in many ways, have lost: a way to move through the deep sorrow of loss, rather than tiptoeing around it.

The Irish wake reminds us that grief is not a burden to be carried alone. When we share the burden, it becomes more bearable. In that sharing, we also open up the possibility for joy. Irish wakes embody the truth that joy and sorrow are not opposites, but companions. When we fully embrace the pain of death—not just as an ending, but as part of the cycle of life—we are better equipped to carry on to the life that awaits us beyond it.

There’s something so important here. And it’s not just poetic, it’s backed by research. An Ulster University study found that prolonged grief disorder, a condition in which deep mourning persists for months or even years, is significantly less common in Ireland than in the UK. Researchers suggest that this may be due to the communal nature of Irish wakes—where friends, family, and neighbors come together to mourn, tell stories, and support the bereaved long before the funeral itself. The Irish literally grieve better, and more effectively.

The difference is readily apparent to so many of us who have experienced both Irish and British funerals. As author Kevin Toolis put it:

“The English never quite understand the Irish wake…why hundreds would queue in the rain to pay respects, share stories, and sit beside the dead…Most have never even seen a corpse, let alone spent the night in its company. They're missing out on our greatest tradition."

Giving grief a voice

In Irish folklore, the Banshee—bean sí, or “woman of the fairies”—is a liminal figure whose mournful cries drift through the night as an omen of impending death. In real life, the keening women were the ones who gave grief its first breath.

Keening—caoinadh in Irish—was once a sacred expression of grief and a central part of the wake. This was not simply a mourning ritual but a vocal eruption of such sorrow and intensity it seemed to shake the walls of a home and carry across the hills.

The keeners (typically performed by the ban chaointe or “women of lament”) stood at the head of the body, setting the tone for the entire wake, their voices both melodic and chaotic. Songs of lament were sung, composed specifically for the deceased, calling upon their ancestors to welcome them. Others were wordless wails, a cacophony of grief made audible. Some of the women might even beat their chests, tear their hair, or throw themselves onto the ground, physically embodying the grief that everyone in the room was feeling but may have been afraid to show. The keeners were essentially alchemists—physically processing and releasing the emotion from their bodies (and those of the other mourners) so that it didn’t end up held and stuck inside—and psychopomps, with their cries believed to help guide the soul to the Otherworld.

Keening is a practice as old as death itself—tracing back continents and centuries, from ancient Egypt and Greece to Indigenous cultures worldwide—it has served the same purpose: to give grief a voice, to unburden the living, and to guide the dead.

With the start of the keening, the wake was officially underway, but as the night wore on, the festivities shifted from sorrow to celebration. Neighbors and friends arrived in waves, drinks flowed, stories and voices grew grander, and sometimes, mischief took over. Pranks were common—one classic involved hiding under the corpse’s bed and shaking it when someone walked in. Apparently, men sometimes lifted the body, making it “dance” to amuse the mourners…can you imagine!? (Please don’t do that to my dead body.)

The wake lasted through the night, and no one left the body alone. Friends and family took turns keeping watch, sitting with the dead until dawn. At midnight, the rosary was said, and by morning, another round of prayers would be whispered before the funeral procession began. When it was finally time for the burial, the body was carried by family and neighbors—sometimes for miles—to the church. In some places, mourners would stop along the way at certain points, letting the deceased “rest” one last time. The final farewell was not just a moment but a journey.

The Great Famine, which wiped out much of Ireland’s poor—the very people who had held onto keening the longest—marked the beginning of its decline. By the 20th century, keening had all but disappeared from Ireland. The Catholic Church frowned upon it, discouraging its practice, branding it too pagan, too primal, and essentially a threat to the Church's patriarchal operating system. Urbanization and modernization drove the final nails into the coffin (forgive the pun); younger generations moved away and found it embarrassing, while funeral homes deemed it outdated.

Reclaiming a forgotten wisdom

I remember sobbing uncontrollably at my mother’s funeral.

My body convulsing, I thought I might throw up or pass out. The grief was pouring out of me at an uncontrollable pace. Maybe, without realizing it, I was tuning into something ancient, something embedded in my bones (my late mother was always a big believer in epigenetics).

Perhaps I was keening. Not in the formal, ritualistic sense, but in the way my ancestors once did—letting grief take its full shape rather than swallowing it whole.

That is, until I did swallow it—in the form of my sister shoving a lorazepam down my throat. At the time, I was grateful. My sobs had turned to gasps, and I could feel the sweat forming, the hot shame of being too much. Too loud. My wailing wasn’t just overwhelming me—it was overwhelming the room. I was drowning out the beautiful words people were trying to say about my mother. I felt like a crying baby at a wedding; a disruption that needed to be removed so that everyone else could focus on the ceremony.

The pill worked. I quieted myself and my grief, but in the process, I also became a shell of who I used to be.

Grief isn’t meant to be swallowed; it’s meant to be set free. And when we force it into quiet corners, medicate it into submission, it doesn’t disappear—it festers. It lingers in our bodies, rewires our brains, and builds up like a toxic poison in our blood. But grief is not poison; grief is love with nowhere to go. And if we do not let it move through us, it will find another way to make itself known.

In the modern world, grief has become taboo. But I can’t help but wonder: Would we be healthier if we let ourselves keen? If we let mourning spill out in waves instead of tidying it up into small, acceptable expressions?

There is something to be learned from the old ways—something that, if we give ourselves permission, might feel surprisingly natural to us.

Our ancestors knew that grief, like love, demands expression—that mourning, when shared with no shame, does not break us—it frees us from a prison of our own making. I believe there is something to reclaim. This is why, in my work as a death doula, I strive to empower people to let it all out—to scream and dance and cry and laugh—to break free of the quiet, to speak up, to give their grief a voice.

Maybe we don’t need to return to lifting corpses or shaking beds (although, I mean, it does sound kinda fun). But perhaps we can learn from keening women at a wake—a voice urging us not to look away from death, but to acknowledge it, to prepare for it. And to let ourselves feel both the pain and the joy of life, love and loss.

So my question for you is:

If you could design your own wake, what would it look like? Would there be keeners? What music would play? What food would be served? And if you’re in a grief process in your own life, do you need to give yourself permission to physically release it?

I’d love to hear your thoughts—comment below or reply with your experiences.

Sláinte—to the living and the dead.

– Maura

I love this. The passage from shattering grief into exuberant joy… we hold every polarity within ourselves, and loss brings them all to the surface. There’s so much wisdom to be honored here

Thank you for this. I think we need to let the grief out. Why we tend to quiet the ones who wail is beyond me. They are in touch with their grief in a way that is beneficial and healing for them and actually for all who hear it. We are not crying for the loved one but for us. We are the ones left with the grief and loss. We feel that and have to let it go. I may want people to have a good time at my wake and funeral, but I would never tell them not to express their grief. Having lived with grief for almost a year now after my wife's death, I know how important it is to let out the agony and pain. What I say to my loved ones is to celebrate life. Travel the world. Go enjoy life to the fullest. That is how I want you to celebrate my life. Laugh, love, and dance.