You know the feeling.

You board a plane full of strangers, longingly look out the window, and land somewhere unfamiliar. You navigate public transit in a foreign language, wander winding streets with no destination, indulge in food and drink, and stand in front of art that takes your breath away. You feel more like yourself than you have in months—braver, lighter, and more alive. The version of you that’s curious, unhurried, and open steps forward.

Travel—especially to a foreign country—is a kind of mini death and rebirth. It’s one of the fastest and most effective ways to lift ourselves out of our routines, disorient our sense of self, and invite us to see the world through new eyes, if only for a few days or weeks. When we step outside of our comfort zone, we become more porous to awe, absurdity, and novelty. In a new place, with new rules, even your inner critic quiets down, and you get to remember what it feels like to just be. In other words, we travel not only to see something new but to find something new within ourselves.

I know this is all cliche—but cliches exist for a reason. The power of travel to change us is real, and if we’re open to it, we’ll experience it each time we set off on another journey to a new place.

As the travel writer Pico Ayer puts it:

“We travel, initially, to lose ourselves; and we travel, next to find ourselves. We travel to open our hearts and eyes and learn more about the world than our newspapers will accommodate… And we travel, in essence, to become young fools again—to slow time down and get taken in, and fall in love once more.”

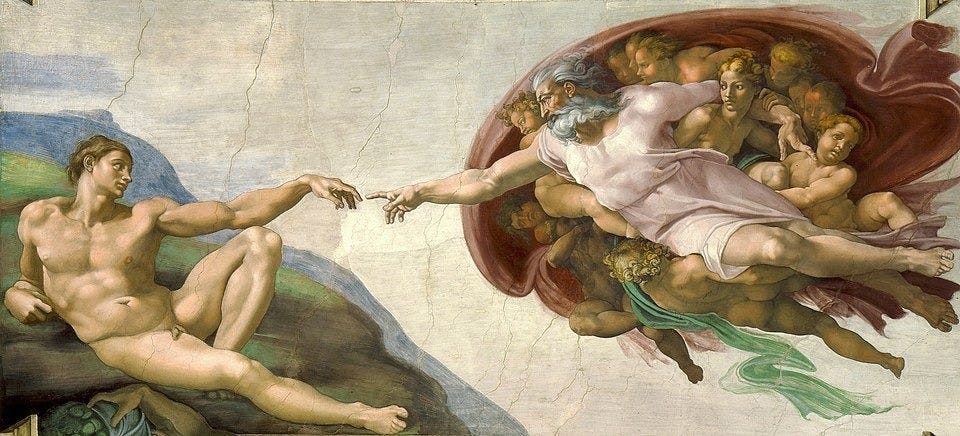

This has all been fresh on my mind. I just got back from some time abroad, visiting Rome, Sicily, and Munich—three very different places that each moved me in their own way. One moment, I was standing in the Sistine Chapel, neck craned toward the ceiling, staring at Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, brushstrokes of a man who didn’t even want the job. At 33, he preferred sculpting to painting (at the time, he had no experience with frescoes), and it took him four years to finish what he saw more as a burden than a masterpiece. It makes me wonder how many great works were forged not from passion, but from persistence—or even servitude.

The next, I was riding a four-wheeler over volcanic rock in Sicily, watching the top of Mt. Etna, smoking in the distance, contemplating my safety.

On my last stop before returning home, I enjoyed a private tour of the Mayer glass workshop in Munich (thanks to my cousin, Alex). Housed in a six-story building in the city center, Mayer has been producing stained glass and mosaics for nearly two centuries. Their work appears in cathedrals, subway stations, and airports around the world—including the only colored glass in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Everywhere I went, I felt more awake (Italian espresso and driving will do that), more aware of time (and also the absence of it), beauty, and my mortality.

Final Boarding Call

It turns out this feeling isn’t just in my head—it’s science. Studies show that travel can rewire your brain, increase neuroplasticity, boost creativity, reduce anxiety, and even improve your personality over time. A 2013 study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology followed German college students who studied abroad. Compared to those who stayed home, the travelers showed measurable gains in openness, agreeableness, and emotional stability—thanks, in part, to diverse social networks and the demands of adapting to new environments.

These same traits—especially openness—don’t just shape how we travel, but how we face life’s biggest questions. People who seek out the unfamiliar are often the same ones willing to face the fact that life ends, and to live well because it does.

Because when you go somewhere unfamiliar, you’re forced to think differently, act differently, and see differently. The neuroscience of travel backs what so many of us feel intuitively: that getting away doesn’t just reset us—it transforms us, as cliche as it sounds.

The late and great Anthony Bourdain said it best:

“Travel isn't always pretty. It isn't always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts, it even breaks your heart. But that's okay. The journey changes you; it should change you. It leaves marks on your memory, on your consciousness, on your heart, and on your body. You take something with you. Hopefully, you leave something good behind."

It’s no wonder that people often travel after a loss, the end of a relationship, a job, a version of life, or a part of themselves they thought was certain. After my mom died, I went to Bali—a trip that changed my understanding of grief and my belief in signs from the other side, but that’s another contemplation for another time.

There’s even a name for it now: grief travel. It’s not about escaping, it’s about allowing ourselves to be lost, to be in the unknown, to lose our familiar reference points. It also gives us the space and time to process our pain. As grief researcher Mary-Frances O’Connor puts it, “grieving requires the difficult task of throwing out the map we have used to navigate our lives.” And what better way to do that—literally and figuratively—than by finding ourselves in a new destination?

Even if you’re not grieving, travel still reminds you of life’s brevity. Like contemplating death, travel wakes us up. It invites us to see with new eyes, to feel everything a little more, a chance to shed old identities, to loosen our grip on certainty, to remember how temporary it all is and how beautiful.

That’s exactly what I felt during my recent travels. What struck me more than the rolling hills of the Italian countryside, the sparkling Mediterranean Sea off Sicily’s coast, or the fresh pasta made that day, was how differently these places relate to time, aging, and death. Here’s what I noticed:

Death as sacred vs death as scary

Some places remind you that you're just passing through this life. Rome is one of them.

In Rome, you don’t have to seek out death—it finds you. It’s carved into stone, painted on ceilings, buried beneath your feet (ever heard of Nero’s palace?). Here, time folds in on itself. You don’t walk on sidewalks, but on cobblestones laid centuries ago, through churches built not just to impress but to outlast. The artwork is so ornate it aches. And underground train construction is perpetually delayed by ancient ruins. You literally can’t take a step forward without hitting the past.

Compare that to America, where death is a disruption and failure, hidden behind euphemisms and anti-aging serums. Here, it’s celebrated and ingrained as part of the architecture of life. At the top of the Spanish Steps, in Trinità dei Monti, I found a quote by Saint Thérèse of Lisieux that caught my eye:

“I am not dying, I am entering life.”

Beneath it, a skull embedded in marble. A reminder: death is only morbid if you miss the point.

I stood there longer than I expected. Stumbling upon this quote and skull felt like a sign. It somehow validated this whole strange quest I’ve been on to normalize talking about death. To make space for the kinds of questions we used to ask, before we started filling every quiet moment with a scroll.

While I was there, a new pope was inaugurated, and the Vatican’s Holy Door was open—a sacred tradition that occurs only every 25 years. Walking through it is said to grant full absolution of your sins. I did it even though I am not religious, because why not? And then, immediately afterward—a bird pooped right on my head.

I stood there, stunned, then started laughing. Was that a sign of divine humor? Cosmic balance? A reminder that grace doesn’t always arrive in the ways we expect? Depending on who you ask, that’s either a positive omen or just bad random chance. In many cultures, including Italy, it’s considered a sign of good luck, prosperity, or unexpected blessings. I’m choosing to go with the latter, regardless of what it really meant. Life can be meaningful even when it doesn't make sense.

Let your lava flow

In Rome, death is sculpted, framed, and preserved, but in Sicily, it simmers beneath your feet. Mt. Etna—Europe’s most active volcano—sits there like a living metaphor: beautiful, unpredictable, always on the verge of letting go.

At the wedding I attended, the volcano loomed in the distance, smoking softly. A week earlier, it erupted. No one considered canceling. In fact, locals said it was a blessing. Better for the mountain to release a little pressure every now and then than build toward something catastrophic, like an eruption that buried the city of Catania in 1669.

Learning that detail made me think: maybe this is the emotional wisdom we’re missing. In the U.S., we’re death-avoidant. We are handing death over to hospitals and funeral homes, instead of caring for the people we love at home and with community. We grieve on a schedule—quickly, quietly, and alone.

But what if we were more like Mt. Etna? What if we allowed small eruptions of grief, sadness, truth—before they became unmanageable? What if we let ourselves talk about death before it happened to us? Maybe we’d be less afraid. Maybe we’d live more fully.

What are you rushing toward?

Travel slows us down—especially in Europe, where it seems to move slower all the time. Where people seem to have a better sense of how to live, not just how to work.

In America, time is something to conquer. We measure, monetize, and optimize it. We glorify the grind, even our vacations come with guilt. We try to pack as much as possible into a day, and we end up needing a vacation from our vacation.

But in Europe, time feels different—less mechanical, more human, softer. Take dinner, for example. In both Rome and Sicily, we sat down to eat around 8 or 9 pm, which is late by American standards, and no one brought us the bill unless we asked. At first, it felt strange, but I grew to cherish this. There was no rush to turn tables, no hovering waiter nudging us along. In fact, once or twice we tried to leave quickly (to make it on time for a tour), and the waiter looked almost offended, as if we were missing the whole point. Because the point isn’t just to eat, it’s to linger, to let the conversation stretch, the wine flow, and time pass.

Some of my favorite moments from the trip were when we sat down for an aperitif (with no dinner reservations to make on time) and I was able to watch and become lost in my surroundings. Locals set up chairs and cards in the middle of the piazza, old men trading stories like currency, while children played soccer. No one was on their phone (except for all the tourists), multitasking, or refreshing social media.

This slow savoring isn’t limited to mealtime. In many parts of Europe, entire cities come to a standstill in August. Shops close. Emails go unanswered. People actually take time off, a month at that! Rest isn’t a reward, it’s a right and a rhythm.

Compare that to the U.S., where some people don’t take their PTO for fear of seeming lazy, where the average vacation is just over a week, and where “out of office” often really means still checking email. We say life is short, but maybe it’s time to rethink what it means to “use our time well.”

It’s easy to think the magic only lives in foreign places (and sure, some towns really do feel like a fairytale), but the real magic isn’t where we go—it’s where we place our time and, more importantly, attention. The true gift of travel is that it snaps us out of autopilot and reminds us we’re all living on borrowed time. So while we’re here: eat slowly, wander instead of walking, and look up more.

When was the last time a trip changed you?

Comment with your experiences—I’d love to know.

– Maura

Makes me want to set off on my next adventure. I’m heading to Malta next Spring and cannot wait to drop into the experience you describe so beautifully!

In retirement, my scheduled routines have become work, and so I travel to break things up. Recently, I returned to Chile and visited my brother and cousins who treated me like visiting royalty. I dined and drank and visited with them as never before due to the fact that I had no schedule or places I had to visit. Our conversations became deeper, our philosophies explained and defended calmly, and our bonds were forevever strengthened, as was the love we were able to share by spending time with each other. Nothing re-energizes one more than taking the time to live in the moment and appreciate what's before them.